Message from Sir Nicholas Mostyn - Judge in the Financial Remedies Awards 2025

Ten years ago, Class Legal staged its inaugural financial remedies conference, the At A Glance Conference. Retitled this year as the Financial Remedies Conference, it remains the finest such conference in the calendar.

DICTIONARY OF THE COURT OF PROTECTION Review by Sir James Munby

Almost a dozen years ago, in September 2013, I was privileged to welcome the very first Dictionary when I wrote the Foreword to the first edition of the Dictionary of Financial Remedies.

15 Apr 2025

Pensions on Divorce: A Practitioner's Handbook - Book Launch

Alex Teanby | 18 Mar 2025 | 2 Minute Read

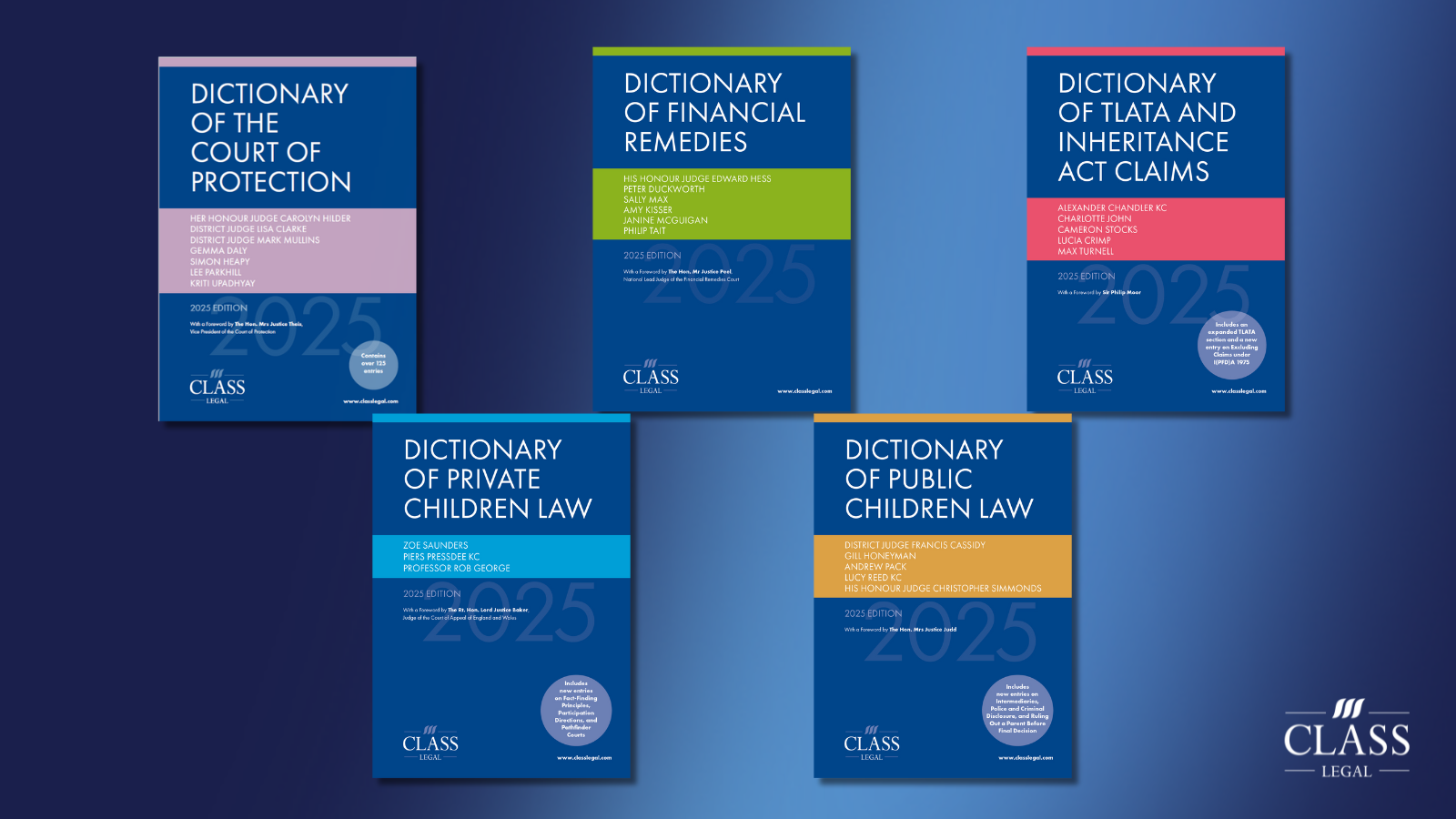

Books to read if you love the Dictionary of Financial Remedies

Alex Teanby | 28 Feb 2025

What titles are new & upcoming in 2025?

Alex Teanby | 24 Feb 2025 | 3 Minute Read

Financial Remedies Awards 2025

To celebrate 10 years since our first ever conference, we are holding our inaugural Financial Remedies Awards.

Alex Teanby | 07 Feb 2025

Your Summer Reading List: The latest titles arriving this summer

The new season calls for an updated bookshelf. Explore our upcoming titles, ready to be added to your summer reading list.

31 Oct 2024

At A Glance: The Must-Have Title

At A Glance 2024-2025 is now available, but what makes this must-have title so essential?

31 Oct 2024

Transparency, Media Attendance and Reporting Transparency | Extract from Dictionary of Public Children Law 2024

Read an exclusive extract from the latest addition to the Dictionary series, Dictionary of Public Children Law 2024.

31 Oct 2024

Everything you need to know about Financial Remedies Practice

Financial Remedies Practice is the only book available with a sole focus on the Family Procedure Rules 2010, where the rule applies specifically to Financial Remedies.

28 Oct 2024

Viewing 1 - 10 of 10 posts